Rescuing Mind from the Machines从机器中拯救心灵¶

** Vincent J. Carchidi agrees with Descartes and friends that our ability to use language creatively distinguishes our minds from computers.Vincent J. Carchidi 同意笛卡尔和朋友们的观点,即我们创造性地使用语言的能力将我们的思想与计算机区分开来。**

The study of artificial intelligence was originally conceived partly as an effort to make sense of the human mind. That is to say, the pursuit of practical computing machines ran parallel to an interest in computing as a model of human cognition. This was present from the start in Alan Turing’s 1950 essay ‘Computing Machinery and Intelligence’. Indeed, some scholars argue that the field of AI moved from a multidisciplinary effort to simulate the workings of the human mind, to a project of literally building human-like intelligence into machines.

人工智能的研究最初部分被认为是为了理解人类的思想。也就是说,对实用计算机器的追求与对计算作为人类认知模型的兴趣是平行的。这在艾伦·图灵 1950 年的文章《计算机与智能》中从一开始就存在。事实上,一些学者认为,人工智能领域从模拟人类思维运作的多学科努力转变为将类似人类的智能构建到机器中的项目。

The shift can be exaggerated; after all, figures such as John von Neumann spoke even in the twentieth century of an approaching technological ‘singularity’. That said, the shift towards desiring human-like artificial intelligence is real, and it has resulted in an ever-intensifying trend that in fact devalues the human mind. Indeed, a routine association of computational models with biological minds in part prompted this warning in Nature Machine Intelligence in December 2024: “The era of machines as deterministic, predictable, and boring objects of fixed structure is coming to an end.” One implication of all this is: we need clarity on the relation between engineered machines like AI systems and biological beings like us, and we need it now.

这种转变可能被夸大了;毕竟,约翰·冯·诺依曼 (John von Neumann) 等人物甚至在 20 世纪就谈到了即将到来的技术“奇点”。也就是说,向渴望类人人工智能的转变是真实的,它导致了一种不断加剧的趋势,实际上使人类的思维贬值。事实上,计算模型与生物思维的常规联系在一定程度上促使 2024 年 12 月在 Nature Machine Intelligence 上发出了这样的警告:“机器作为固定结构的确定性、可预测性和无聊对象的时代即将结束。这一切的一个含义是:我们需要明确像 AI 系统这样的工程机器和像我们这样的生物之间的关系,我们现在就需要它。

Descartes’ Turing Test 笛卡尔图灵测试¶

AI poses anew a centuries-old challenge: What, if anything, distinguishes the human mind from the workings of a machine? This problem traces back at least to René Descartes (1596-1650), who put it as follows: Suppose one comes across a creature that bears the outward appearance of a human being and moves through the world like a human. How are we to determine whether this being has a soul – or a mind – like ours?

AI 提出了一个由来已久的新挑战: 人类的大脑与机器的运作有什么区别(如果有的话)? 这个问题至少可以追溯到勒内·笛卡尔(René Descartes,1596-1650),他这样说:假设一个人遇到一个外表像人的生物,像人一样在世界上移动。我们如何确定这个存在是否具有像我们一样的灵魂或思想?

Descartes’ problem of other minds reveals that our current dilemma in understanding them is not new, and that this whole topic has deep ties with machine history. The Large Language Models (LLMs) of recent fascination are merely the latest iteration of this challenge.

笛卡尔对其他思想的问题揭示了我们目前在理解他们方面的困境并不新鲜,而且整个话题与机器历史有着深厚的联系。最近令人着迷的大型语言模型 (LLM) 只是这一挑战的最新版本。

The cultural influences on Descartes’ thought help us understand why he posed this problem – why he thought it so important to distinguish humans from machines. For many Christians in Europe even before Descartes, machines were a common part of life. As Jessica Riskin details in The Restless Clock (2016), life-like automata of various kinds – humans, animals, angels – were constructed for use in churches and cathedral clocks. Such machines could have an active presence in the world, displaying, as Riskin puts it, ’a vital and even a divine agency.” This perception of agency was thus both attributed both to living beings and to (some) machines.

笛卡尔思想的文化影响有助于我们理解他为什么提出这个问题——为什么他认为区分人类和机器如此重要。对于许多欧洲基督徒来说,甚至在笛卡尔之前,机器就是生活中常见的一部分。正如杰西卡·里斯金 (Jessica Riskin) 在 《不安的时钟 》(2016 年)中所详述的那样,各种栩栩如生的自动机——人类、动物、天使——被建造出来用于教堂和大教堂的时钟。这种机器可以在世界上 活跃 存在,正如里斯金所说,显示出“一种至关重要甚至神圣的机构”。因此,这种对能动性的感知既归因于生物,也归因于(一些)机器。

However, in the 16th century the Reformation, triggered a shift in how the natural world was perceived. In the eyes of religious reformers, machines became, as Riskin elaborates, ‘empty of spirit’ by virtue of their composition merely of mechanical parts. Furthermore, the ‘mechanical philosophy’ – the idea that all of existence’s diverse phenomena can be accounted for as though the world were a complex machine – was gaining prominence. The natural world’s mechanical properties were separated from divinity and agency; thus the life-like automata that once accompanied Christian liturgies were no longer in possession of spirit. Their construction from artificial components made them mere machines lacking agency.

然而,在 16 世纪,宗教改革引发了人们对自然世界的看法的转变。正如里斯金所阐述的那样,在宗教改革者眼中,机器变得“没有精神”,因为它们仅由机械部件组成。此外,“机械哲学”——即存在的所有不同现象都可以像世界是一台复杂的机器一样被解释——正在变得越来越突出。自然界的机械特性与神性和能动性是分开的;因此,曾经伴随基督教礼拜仪式的栩栩如生的自动机不再具有精神。它们由人造部件构成,使它们成为缺乏能动性的机器。

Human uniqueness required something beyond the mere complex organization of matter. So although Descartes, according to Philip Ball, “set out a view of the human body as a wondrous mechanism of pumps, bellows, levers, and cables” (How Life Works, 2023), these components are for Descartes, “animated by the divinely granted rational soul”, which is connected to but independent of the body.

人类的独特性需要超越单纯的复杂物质组织的东西。因此,尽管根据菲利普·鲍尔 (Philip Ball) 的说法,笛卡尔“将人体视为由泵、风箱、杠杆和电缆组成的奇妙机制”( 《生命如何运作 》,2023 年),但这些组件对笛卡尔来说,“由神圣赋予的理性灵魂驱动”,它与身体相连但独立于身体。

The metaphysical rubber begins hitting the road for Descartes at roughly this juncture. He poses his problem of other minds in his 1637 book Discourse on Method thus: Imagine observing a mechanical body that exhibits all of the outward appearances of a human being – it appears to have the same skeletal and muscular structure, the same layout of veins and arteries, and it exercises the same movements of the body as any human might. How, Descartes asks, can we distinguish between this body and an actual human being, if each is ultimately the product of a complex network of mechanical components? He then argues they can be distinguished through ‘’two most certain tests”, one of which is a language test. Descartes argues that how human beings use language has a distinctive character, inexplicable in purely mechanical terms and the detection of this distinctive character indicates that we are not observing a machine, but a creature with a mind like our own:

笛卡尔的形而上学橡胶大约在这个关头开始上路。他在 1637 年的著作《 方法论 》中提出了他对其他思想的问题:想象一下,观察一个机械身体,它表现出人类的所有外表——它似乎具有相同的骨骼和肌肉结构,相同的静脉和动脉布局,并且它行使与任何人类相同的身体运动。笛卡尔问道,如果每个身体和真实的人 最终都是复杂的机械部件网络的产物 ,我们该如何区分它们呢?然后,他认为可以通过“两个最确定的测试”来区分它们,其中一个是 语言 测试。笛卡尔认为,人类如何使用语言具有独特的特征,用纯粹的机械术语来说是无法解释的,而对这种独特特征的检测表明,我们不是在观察机器,而是一个拥有与我们自己一样的思想的生物:

“Of these [tests] the first is that they could never use words or other signs arranged in such a manner as is competent to us in order to declare our thoughts to others: for we may easily conceive a machine to be so constructed that it emits vocables, and even that it emits some correspondent to the action upon it of external objects which cause a change in its organs… but not that it should arrange them variously so as appositely to reply to what is said in its presence, as men of the lowest grade of intellect can do ” (Emphases added).

“在这些[测试]中,首先是它们永远不能使用 我们能胜任 的文字或其他符号来 向他人宣告我们的思想 :因为我们很容易想象一台机器的结构是这样的,它发出了声息,甚至它发出了一些与外部物体的作用相对应的东西,这些物体导致它的器官发生了变化......但并不是说它应该以不同的方式安排它们,以便 适当地回答在它面前所说的话,就像智力最低的人可以做的那样 “(强调后加)。

So, according to Descartes, one may judge that a being possesses a mind like ours if its language-use meets certain criteria. One is that the subject’s speech is intelligible (‘competent to us’). Another is that it uses speech to express its thoughts (‘declare’ them). The third is that it combines words in an appropriate fashion (‘arrange them variously’ as ‘appositely to reply’). Finally, they should do so habitually, without specialized intelligence (‘as men of the lowest grade of intellect can do’). Descartes also rules out two language conditions as insufficient for inferring the presence of a reasoning mind: the mere output of words (‘emits vocables’), and the mere output of words as a direct result of contact with external stimuli (‘correspondent to the action upon it’). Also, on Riskin’s reading of the history of automata, it was the ‘limitlessness of interactive language’ that stopped a physical mechanism from reproducing human linguistic ability. So ordinary language use, therefore, was granted the status of non-mechanical – attributed instead to, as Descartes would put it, a ‘rational soul’.

因此,根据笛卡尔的说法,如果一个人的语言使用符合某些标准,那么他可以判断一个人拥有像我们一样的思想。一个是主体的言语是可理解的(“胜任我们”)。另一个是它使用语言来表达它的想法(“宣布”它们)。第三个是它以适当的方式组合单词('arrange them variously' 作为 'appositely to reply')。最后,他们应该习惯性地这样做,没有专门的智力(“就像智力最低等级的人可以做的那样”)。笛卡尔还排除了两种语言条件不足以推断推理思维的存在:单纯的词语输出(“发出声波”),以及单纯的词语输出作为与外部刺激接触的直接结果(“对应于对它的行动”)。此外,在里斯金对自动机历史的解读中,正是“交互式语言的无限性”阻止了物理机制复制人类的语言能力。因此,普通的语言使用被赋予了 非机械 的地位——正如笛卡尔所说,它被赋予了“理性的灵魂”。

Descartes’ initial remarks on the language test were extended by his followers, including Géraud de Cordemoy. Yet, this problem of infinite linguistic generativity from a finite physical being stymied further inquiry until long after the mechanical philosophy’s demise.

笛卡尔对语言测试的最初评论得到了他的追随者的扩展,包括 Géraud de Cordemoy。然而,这个来自有限物理存在的无限语言生成性的问题阻碍了进一步的探究,直到机械哲学消亡很久之后。

Artificial Intelligence Eye Mohamedgu123 Creative Commons 4

人工智能之眼 Mohamedgu123 知识共享 4

Computing Language Computability计算语言可计算性¶

Alan Turing’s (1912-54) genius was to prove it a possibility: “It is possible to invent a single machine which can be used to compute any computable sequence” (‘On Computable Numbers’). He demonstrated that in principle a single ‘Turing machine’, with a fixed structure, could carry out every computation that can be carried out by any machine. Put simply: infinite generation from finite means is possible. The establishment of general computability theory in the early twentieth century gave us the tools to study this possibility.

艾伦·图灵(Alan Turing,1912-54 年)的天才之处在于证明了这种可能性:“有可能发明一台机器来计算任何可计算序列”(《论可计算数》)。他证明,原则上,具有固定结构的单个“图灵机”可以执行任何机器可以执行的所有计算。简而言之:从有限手段无限产生 是 可能的。20 世纪初广义可计算性理论的建立为我们提供了研究这种可能性的工具。

Linguists in the early-to-mid twentieth century reformulated Descartes’ problem along lines enabled by computability theory. But just as Descartes first articulated the language test within a problematic framework – the mechanical philosophy from which human language use was exempted – computability theory re-shaped the problem of artificial language use in ways that similarly disturb our efforts at explanation. For computability theory has its own limits. For instance, notice that the study of a finite biological system capable of infinite generativity says nothing about the actual use of the system. So computability theory provides no direct insight into ordinary language use – the original Cartesian problem. Thus, a distinction between competence and performance is drawn: a person might be able to speak with infinitely more variety and facility than they actually do speak. This distinction is crucial. The tools that enable us to study the infinite generativity of a finite biological system, residing within the human brain’s language faculty, are suited only to the task of characterizing the system. The use of this ability in actual linguistic production is another matter entirely. Today, this ‘creative’ aspect of language use occupies ‘linguistic performance’ inquiry. Contemporary linguists and philosophers have formalized Descartes’ and Cordemoy’s observations about human linguistic possibility into three conditions:

20 世纪早期到中期的语言学家按照可计算性理论的思路重新表述了笛卡尔的问题。但是,正如笛卡尔首次在一个有问题的框架中阐明语言测试一样——人类语言使用被排除在机械哲学之外——可计算性理论以同样干扰 我们 解释工作的方式重塑了人工语言使用的问题。因为可计算性理论有其自身的局限性。例如,请注意,对能够产生无限生成的有限生物系统的研究并没有说明该系统的实际用途。因此,可计算性理论没有提供对普通语言使用的直接见解 - 最初的笛卡尔问题。因此, 能力和 表现 之间就有了区别:一个人的说话可能比 他们实际说话 的种类和技巧要多得多。这种区别至关重要。使我们能够研究存在于人脑语言能力中的有限生物系统的无限生成性的工具,只适合于描述 系统 的任务。 在实际 的语言生产中使用这种能力完全是另一回事。今天,语言使用的这个“创造性”方面占据了“语言表现”的探究。当代语言学家和哲学家将笛卡尔和科德米对人类语言可能性的观察正式归纳为三个条件:

Stimulus-Freedom: Humans can produce new expressions that lack any one-to-one relationship with their environments. Generally, stimuli in a human’s local environment appear to elicit utterances, but not cause them. If human language use is not affixed in some determinate, predictable fashion to stimuli, then language use is not directly caused by situations. Among other things, this means that meaningful expressions can be generated about environments far-removed from the local context in which the person speaks; or even about imaginary contexts. The contrast with animal communication is striking here. For animals, communication is restricted to the local context of its use. Human language use is, in sharp contrast, detachable: a pillar of the human intellect may be the ability to detach oneself from the circumstances in which cognitive resources are deployed without reliance on stimuli to do so. In other words, we can think for ourselves.

刺激自由 :人类可以产生与环境缺乏任何一对一关系的新表达。一般来说,人类局部环境中的刺激似乎会 引发 话语,但不会 引起 话语。如果人类语言的使用不是以某种确定的、可预测的方式附加到刺激上,那么语言的使用就不是由情境直接引起的。除其他外,这意味着可以生成关于远离人说话的当地环境的有意义的表达;甚至关于想象的背景。与动物交流的对比在这里非常明显。对于动物来说,交流仅限于其使用的当地环境。与此形成鲜明对比的是,人类语言的使用是可分离的:人类智力的一个支柱可能是能够将自己从认知资源部署的环境中抽离出来,而不依赖刺激来做到这一点。换句话说,我们可以自己思考。

Unboundedness: Human language use is not confined to a pre-sorted list of words, phrases, or sentences (as it is with LLMs). Instead, there’s no fixed set of utterances humans can produce. This is the infinite productivity of human language – the unlimited combination and re-combination of finite elements into new forms that convey new, independent meanings.

无界性 :人类语言的使用并不局限于预先排序的单词、短语或句子列表(就像 LLM 一样)。相反,人类可以生成一组固定的话语。这就是人类语言的无限生产力——将有限元素无限地组合和重新组合成新的形式,传达新的、独立的含义。

Appropriateness to Circumstance: That human language use is stimulus-free can be revealing when we reflect that utterances are routinely appropriate to the situations in which they are made and coherent to others who hear them. If human language use is both stimulus-free and not caused by situations, this means its relation to one’s environment must be the more obscure relation of appropriateness. Indeed, language use “is recognized as appropriate by other participants in the discourse situation who might have reacted in similar ways and whose thoughts, evoked by this discourse, correspond to those of the speaker” (Language and Problems of Knowledge, Noam Chomsky, 1988).

适合环境 :当我们反思话语通常适合于它们所处的情境并且对听到它们的其他人来说是连贯的时,人类语言的使用是无刺激的,这可能很能说明问题。如果人类语言的使用既无刺激又不是由情境 引起的 ,这意味着它与环境的关系必须是更模糊的 适当性 关系。事实上,语言使用“被话语情境中的其他参与者认为是适当的,他们可能以类似的方式做出反应,并且这种话语所唤起的思想与说话者的想法相对应”( 语言与知识问题 ,Noam Chomsky,1988 年)。

Only when all three conditions are simultaneously present does language use take on its special human character. As Chomsky summarized it:

只有当所有三个条件同时存在时,语言使用才具有其特殊的人类特征。正如乔姆斯基所总结的那样:

“man has a species-specific capacity, a unique type of intellectual organization which cannot be attributed to peripheral organs or related to general intelligence and which manifests itself in what we may refer to as the ‘creative aspect’ of ordinary language use – its property being both unbounded in scope and stimulus-free. Thus Descartes maintains that language is available for the free expression of thought or for appropriate response in any new context and is undetermined by any fixed association of utterances to external stimuli or physiological states (identifiable in any noncircular fashion)”

“人类具有一种物种特有的能力,一种独特的智力组织,它不能归因于外周器官,也不能与一般智力相关,它表现在我们所说的普通语言使用的'创造性方面'——它的特性既是无限的,又是无刺激的。因此,笛卡尔坚持认为,语言可用于思想的自由表达或任何新环境中的适当反应,并且不受话语与外部刺激或生理状态的任何固定关联(以任何非循环方式识别)所决定。

(Noam Chomsky, Cartesian Linguistics, 1966).

(诺姆·乔姆斯基, 笛卡尔语言学 ,1966 年)。

It is a distinctively human trait to use language in a manner that is simultaneously stimulus-free, unbounded, yet appropriate and coherent to others. Such language use is neither determined (by a stimulus) nor random (inappropriate). This ability enables people to deploy their intellectual resources to any problem, or to create new problems altogether, putting our shared cognitive capacities to use across contexts at will. It is little wonder then why Descartes assigns such importance to language use in his test for other minds. A being that uses language in only one or two of the three ways described can be explained in mechanical terms – but the presence of all three is something that modern technology lacks the tools to create.

以一种同时无刺激、无限制但对他人适当和连贯的方式使用语言是一种独特的人类特征。这种语言的使用既不是 (由刺激 ) 决定 的,也不是 随机 的 (不适当)。这种能力使人们能够将他们的智力资源部署到任何问题上,或者完全创造新的问题,随意将我们共享的认知能力用于各种情境。那么,难怪笛卡尔在他对其他思想的测试中如此重视语言的使用。一个只以所描述的三种方式中的一种或两种使用语言的生物可以用 机械 术语来解释——但这三种方式的存在是现代技术缺乏创造的工具。

There’s no quick fix for this. First, it’s difficult to adequately specify what counts as ‘appropriateness’ – but we would not do away with it, for some uses of language are inappropriate and incoherent. Likewise, we may be tempted to assign to human language a controlling stimulus, not in the local environment, but in an internal state: perhaps the brain causes language use. Yet, the limits of explanation again disturb our inquiry here, just as they did the Cartesians’: physical causality, even in an internal (brain) state, is deficient as a ‘governing principle’ for language use, since it only explains the physical combination of linguistic elements, not the generation of meaning. Generally speaking, it does not account for the attribution of meaning to a remark. Nor can the term ‘stimulus’ be applied to any internal brain state without emptying the term of its present psychological meaning.

这个问题没有快速的解决办法。首先,很难充分指定什么才算是“适当”——但我们不会取消它,因为某些语言的使用 是 不恰当和不连贯的。同样,我们可能很想给人类语言分配一种控制性刺激,不是在局部环境中,而是在内部状态中:也许是大脑导致了语言的使用。然而,解释的局限性再次扰乱了我们在这里的探究,就像他们所做的那样:物理因果关系,即使在内部(大脑)状态下,作为语言使用的“支配原则”也是不足的,因为它只能解释语言元素的物理组合,而不是意义的产生。一般来说,它不考虑评论的含义归属。“刺激”一词也不能应用于任何内部大脑状态,而不清空该术语目前的心理含义。

Still from I, Robot

《我,机器人》 剧照

I, Robot image © 20th Century Fox 2004

I,机器人 图像 © 20 世纪福克斯 2004

Back to the Machines返回机器¶

We return to the present, where the need to distinguish humans from machines made in our image remains strong. As Paolo Bory argues, technology firms who use the spectacle of human-machine showdowns, are in effect reintroducing Descartes’ problem to contemporary audiences (Deep New, 2019). While these firms’ aims are not intellectual, the resulting problem is similar, we’re confronted with a machine bearing, in either form or output, the image of humanity, and we’re being guided toward the idea that such machines have minds like ours. Existential doubt and an impetus to redefine humanity are only a few steps away. But do modern AI-enabled machines exhibit the creative aspects of language use? A reasonable (and honest) observation of LLMs reveals that they do not. They are:

我们回到现在,将人类与按照我们的形象制造的机器区分开来的需求仍然很强烈。正如 Paolo Bory 所说,利用人机对决奇观的科技公司,实际上是在将笛卡尔的问题重新介绍给当代观众( Deep New,2019 年)。虽然这些公司的目标不是智力上的,但由此产生的问题是相似的,我们面对的是一台机器,无论是形式还是输出,都带有人类的形象,我们被引导到这样的机器拥有与我们一样的思想的想法。存在主义的怀疑和重新定义人性的动力仅一步之遥。但是,支持 AI 的现代机器是否表现出语言使用的创造性方面?对 LLM 的合理(和诚实)观察表明它们没有。他们是:

Stimulus-Controlled: The output of a Large Language Model is predictably and inextricably tied to the input it receives. It transforms its input into an output by statistically manipulating a dataset. This means three things: (1) LLMs will generate an output having received an input, unless instructed to the contrary; (2) The operation performed over the input value is determined; it’s a product of the internal programming and external prompting; (3) The LLM will not alter the process of transforming an input into an output. So LLMs are fundamentally input-output devices, unlike the creative human mind.

刺激控制 :大型语言模型的输出与它接收到的输入是可预测且密不可分的。它通过统计作数据集将其输入转换为输出。这意味着三件事:(1) LLM 将在 收到输入后生成输出,除非有相反的指示;(2) 确定 对输入值执行的作;它是内部编程和外部提示的产物;(3) LLM 不会改变将输入转换为输出的过程。因此,LLM 从根本上说是输入输出设备,与创造性的人类思维不同。

Weakly Unbounded: Though LLMs are currently the subject of an ongoing debate concerning the implications for generative linguistics, the debate is often misframed. To be sure, LLMs can generate new text (converted from existing examples of language use) according to a specific configuration acquired during their training. This may be considered a ‘weak’ unboundedness. However, figures such as Descartes and Cordemoy were not concerned with the organization of strings of words into particular configurations; their concern was with the expression of thought; with the contents of one’s mind. In contemporary generative linguistics the productivity of language use that is being studied is the ability to generate an unbounded array of form/meaning pairs, not ‘the organization of strings’ (‘A Model for Learning Strings Is Not a Model of Language’, Murphy and Leivada, 2022). At least three reasons suggest LLMs do not achieve strong unboundedness. First, the persistence of distortions in their outputs and deficiencies or inconsistencies in their instruction-following indicate that they are not generating form/meaning pairs – showing that they have no concept of the meaning of the linguistic strings they create. Second, their training procedures are highly idealized compared to human language acquisition: they’re not in the world learning how to use language in response to experiences, as humans are. Third, state-of-the-art models like OpenAI’s, fail to represent principles of linguistic structure, but instead work through manipulating already existing texts (Murphy et al., ‘Fundamental Principles of Linguistic Structure are Not Represented by o3,’ 2025).

弱无界 :尽管 LLM 目前是关于生成语言学影响的持续辩论的主题,但这种争论经常被错误地界定。可以肯定的是,LLM 可以根据训练期间获得的特定配置生成新文本(从现有的语言使用示例转换而来)。这可能被认为是 'weak' 无界。然而,笛卡尔和科德莫伊等人物并不关心将单词字符串组织成特定的配置;他们关心的是思想的表达;与一个人的思想内容。在当代生成语言学中,正在研究的语言使用生产力是生成无界的形式/意义对数组的能力,而不是“字符串的组织”(“学习字符串的模型不是语言的模型”,Murphy 和 Leivada,2022 年)。至少有三个原因表明 LLM 没有实现强无界性。首先,他们输出中持续存在的扭曲和他们指令遵循中的缺陷或不一致表明他们没有生成形式/意义对——这表明他们对他们创建的语言字符串的含义没有概念。其次,与人类语言习得相比,他们的训练程序高度理想化:他们不像人类那样在世界上学习如何使用语言来回应经验。第三,像 OpenAI 这样的最先进的模型无法表示语言结构的原则,而是通过纵已经存在的文本来工作(Murphy 等人,“语言结构的基本原则不由 o3 表示”,2025 年)。

Functionally Appropriate Only: That LLMs are stimulus-controlled means that they lack humans’ ‘obscure’ condition of appropriateness in their language use. Being stimulus-controlled means they are not ‘inclined’ in certain ways, but rather, ‘impelled’ to do so. Therefore the question of choosing language for its appropriateness does not arise. The transformation of an input value into an output value based on internal programming and external instructions means that LLMs’ outputs are caused by stimuli, rather than being elicited by them.

仅在功能上适当 :LLM 是刺激控制的,这意味着它们在语言使用中缺乏人类对 适当性的 “模糊”条件。被刺激控制意味着他们没有以某种方式“倾向于”这样做,而是“被迫”这样做。因此,不存在根据其适当性选择语言的问题。根据内部编程和外部指令将输入值转换为输出值意味着 LLM 的输出是由刺激 引起的 ,而不是由刺激 引起的 。

For these reasons, we can see that LLMs do not meet the three criteria of Descartes’ test for minds. They fail to demonstrate the creative aspect of language use characteristic of humans.

由于这些原因,我们可以看到 LLM 不符合笛卡尔的心智检验的三个标准。他们未能展示人类语言使用特征的创造性方面。

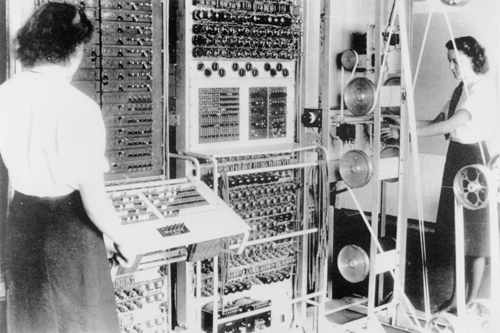

Colossus Mark 2 codebreaking computer being operated by Dorothy Du Boisson (left) and Elsie Booker (right), 1943

1943 年,Dorothy Du Boisson(左)和 Elsie Booker(右)作的 Colossus Mark 2 密码破译计算机

Human Outputs 人力产出¶

What is the significance of this for human self-understanding? I have two immediate lines of thought, one directly related to LLMs, and another related more broadly to the study of human nature.

这对人类的自我理解有什么意义呢?我有两个直接的思路,一个与法学硕士直接相关,另一个与人性研究更广泛地相关。

For one thing, this view reframes recent philosophical perspectives on the significance of LLMs. For example, Tobias Rees argued that ChatGPT-3 was just as epoch-breaking as Descartes’ Discourse on Method once was – with engineers having “experimentally established a concept of language at the center of which does not need to be the humans” (Non-Human Words, 2022). Moreover, Jonathan Birch, referencing Descartes, argues that LLMs “add great urgency to a question… what kinds of linguistic behaviour are genuine evidence of conscious experience, and why?” (The Edge of Sentience, 2024). These perspectives take Descartes’ remarks without linking them to the crucial theoretical accommodations of the twentieth century whereby the creative aspects of language use have been formalized. That LLMs do not replicate this way of using language is not particularly surprising – although a reassertion of human intellectual freedom is in order. LLMs are simply a different type of thing.

首先,这种观点重新构建了最近关于 LLM 重要性的哲学观点。例如,托比亚斯·里斯 (Tobias Rees) 认为,ChatGPT-3 与笛卡尔的 《方法论 》一样具有划时代意义——工程师们“通过实验建立了一个语言概念,其中心不需要是人类”( Non-Human Words,2022 年)。此外,乔纳森·伯奇 (Jonathan Birch) 引用笛卡尔的话,认为 LLM“为问题增加了极大的紧迫性......什么样的语言行为是有意识体验的真正证据,为什么?( 《感知的边缘 》,2024 年)。这些观点接受了笛卡尔的评论,但没有将它们与 20 世纪的关键理论调整联系起来,在那里,语言使用的创造性方面已经正式化。LLM 没有复制这种使用语言的方式并不特别令人惊讶——尽管重新主张人类的智力自由是必要的。LLM 只是一种不同类型的事物。

These ideas also raise a distinction between agency and intellectual freedom. Ball, noting biology’s traditional resistance to the notion of agency, contends that agency is nonetheless observable in commonplace creatures like fruit flies and cockroaches. There it consists of two components: (1) The ability to produce different responses to identical or equivalent stimuli; and (2) The ability to select among such responses in a goal-directed fashion. Yet neither condition entails a creative use of the organism’s cognitive abilities. And remember, human language use is neither deterministic nor random. A fruit fly that flies with random variation in its turning movements is not demonstrating free will. A cockroach that runs from the movement of air in a random path, is not free of the initial stimulus. Moreover, these goal-oriented behaviors have nothing analogous to appropriateness in language use. Finally, neither organism can be said to have a storehouse of thoughts relentlessly being generated throughout their lives; a storehouse that has its contents identified, retrieved, and reassembled for whatever situation or problem by the agent.

这些想法还提出了 能动 性和知识自由 之间的区别。鲍尔指出,生物学传统上对能动性概念的抵制,他认为,尽管如此,在果蝇和蟑螂等常见生物中也可以观察到能动性。它由两个组成部分组成:(1) 对相同或等效刺激产生不同反应的能力;(2) 以目标为导向的方式在此类响应中进行选择的能力。然而,这两种情况都不需要 创造性 地使用生物体的认知能力。请记住,人类语言的使用既不是确定性的,也不是随机的。一只果蝇如果飞行的转动动作是随机变化的,那么它就没有表现出自由意志。蟑螂从空气的随机路径运动中逃跑,并非没有最初的刺激。此外,这些以目标为导向的行为与语言使用的适当性没有任何可比性。最后,这两个有机体都不能说在其一生中都有一个无情产生的思想仓库;代理针对任何情况或问题识别、检索和重新组装其内容物的仓库。

The philosophical problem runs deeper. Although some scholars argue that language is not necessary for thought, and is best conceived as a tool for communication, this neglects the original Cartesian problem (‘Language Is Primarily a Tool for Communication Rather than Thought’, Fedorenko et al, 2024). Just as the behaviourist B.F. Skinner stretched concepts like stimulus-control so far as to void them of scientific content, researchers today risk stretching concepts like communication to account for the otherwise ‘useless’ tool of language – a tool that, despite what they say, can be appropriately recruited for the deployment of cognitive and intellectual resources over an unbounded range at will (‘Language Is a ‘Quite Useless’ Tool’, Watumull, 2024).

哲学问题更深。尽管一些学者认为语言不是思考所必需的,最好将其视为 一种交流 工具,但这忽略了最初的笛卡尔问题(“语言主要是交流工具而不是思考”,Fedorenko 等人 ,2024 年)。正如行为主义者 B.F. Skinner 将 刺激控制 等概念延伸到使它们与科学内容无关的程度一样,今天的研究人员冒着将交流等概念延伸到解释原本“无用”的语言工具的风险——不管他们怎么说,这个工具都可以被适当地招募来随意在无限的范围内部署认知和智力资源(“语言是一种'相当无用'的工具”, Watumull,2024 年)。

Much more could be said, but it is clear that contemporary AI does not meet Descartes’ original language challenge, nor do conceptions of the human mind’s freedom advance with sufficient clarity on an ‘computational’ analogy.

可以说得更多,但很明显,当代人工智能无法满足笛卡尔的原始语言挑战,人类思维自由的概念也没有在“计算”类比上取得足够清晰的进展。

Whether future AI systems could replicate true human linguistic behavior is an open question. There are reasons to doubt it. Human language use being neither determined nor random yet appropriate seems to put it beyond the scope of computation per se. The problem is not likely to be evaded by inserting ‘an added element of randomness or noise’ into a system to induce low-level indeterminacy, as Kevin Mitchell tentatively suggests (Free Agents, 2025).

未来的 AI 系统能否复制真实的人类语言行为是一个悬而未决的问题。我们有理由怀疑它。人类语言的使用既不是确定的,也不是随机的,但又是适当的,这似乎使它超出了计算 本身 的范围。正如凯文·米切尔 (Kevin Mitchell) 试探性地建议的那样,通过在系统中插入“额外的随机性或噪声元素”以诱导低级不确定性,不太可能避免这个问题( Free Agents,2025)。

Human beings are willfully creative creatures. “It is remarkable,” James McGilvray writes, “that everyone routinely uses language creatively, and gets satisfaction from doing so” (Cambridge Companion to Chomsky, 2005). The mind “can also be freed from current practical concerns to speculate and imagine.” In all this, humanity is an unusual species – one with an instinctive ability to use its cognitive abilities creatively, and which willingly wanders into what Larry Briskman (echoing Albert Einstein) describes as the darkness, attempting to ‘’shed light where none has been shed before…” (Creative Product and Creative Process in Science and Art, 1980).

人类是故意创造的生物。詹姆斯·麦吉尔夫雷(James McGilvray)写道:“很了不起,每个人都经常创造性地使用语言,并从中获得满足感”( Cambridge Companion to Chomsky , 2005)。头脑“也可以从当前的实际问题中解脱出来,进行猜测和想象”。在这一切中,人类是一个不寻常的物种——具有创造性地利用其认知能力的本能,并且愿意徘徊在拉里·布莱斯曼(Larry Briskman)(与阿尔伯特·爱因斯坦相呼应)所描述的 黑暗 中,试图“在以前从未被照亮的地方散发出光明......”( 科学与艺术中的创意产品和创意过程 ,1980 年)。

This is the species that confronts AI. If we are thrown into self-doubt by existing AI systems that do not have minds, then it is incumbent on us to rescue the human mind from a misunderstanding entirely of our own making.

这就是 AI 面临的物种。如果我们被没有思想的现有人工智能系统陷入自我怀疑,那么我们有责任将人类思想从完全由我们自己造成的误解中拯救出来。

© Vincent J. Carchidi 2025

© 文森特 J. 卡奇迪 2025

Vincent Carchidi is an independent researcher in cognitive science and the philosophy of mind, with an interest in artificial intelligence.

Vincent Carchidi 是认知科学和心灵哲学的独立研究员,对人工智能感兴趣。